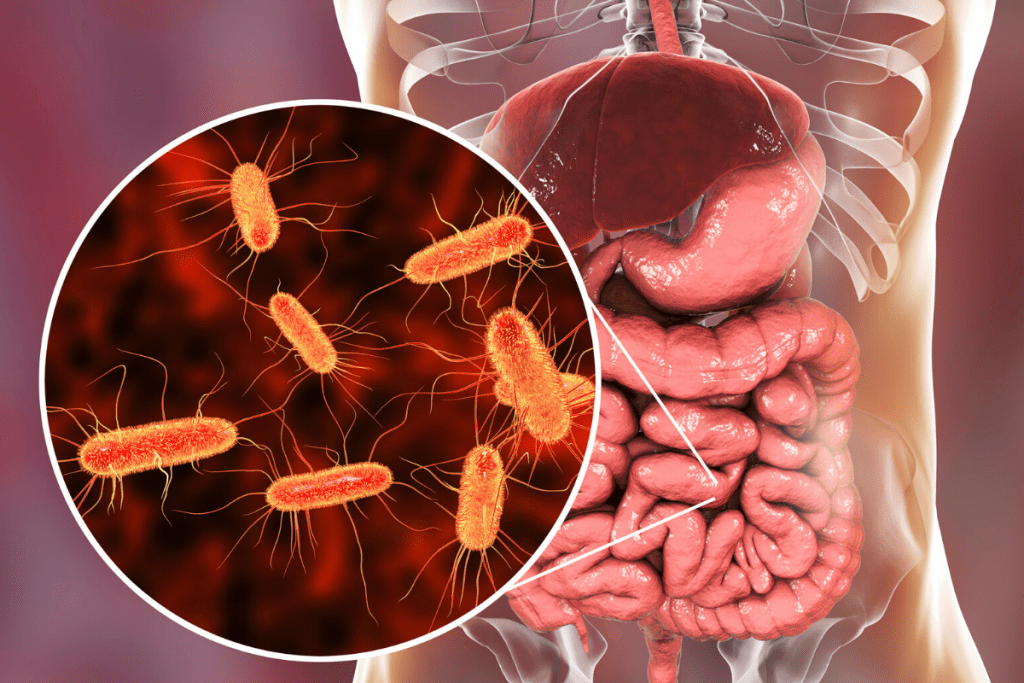

In recent years there has been a significant increase in research exploring the relationship between bacteria, the gut microbiota and human health. With certain imbalances in the gut microbiome being highly associated with a wide range of health conditions, specific underlying mechanisms are becoming understood.

This research into the human gut microbiome is partly aimed at deepening the understanding of human health. As well as this, research is also focused on gathering information to guide clinical recommendations and create targeted and personalised treatment approaches for a wide range of health conditions.

The gut microbiome supports human health in a variety of ways that include:

- Modulating the immune system

- Managing inflammation

- Supporting digestive

- Balancing energy levels

These organisms of the microbiota/microbiome provide a defence against less beneficial organisms that might pose a health risk. They do this by outcompeting these less beneficial organisms in the gut microbiome for nutrition and other forms of competition. [Source: PubMed]

At the moment we know that these beneficial bacteria help to modulate our immune system, promote ‘normal’ gut movements, improve nutritional status through vitamin synthesis (eg B vitamins and vitamin K), metabolism regulation, mood management and production of beneficial compounds called short chain fatty acids (SCFA).

The gut microbiome also influences our ability to process pharmaceutical medications in the gut which may influence their action.

What is The Human Gut Microbiome

While the human body has a total microbial community which is described as the microbiome, the gut microbiome specifically refers to the organisms within the digestive tract.

The microbial community within the gut microbiota/microbiome not only contains bacteria but other species such as parasites, archaea, fungi and viruses.

The gut microbiome is a densely populated community. Not only does the microbiome contains a high concentration of organism but it also contains 3.3 million genes. When compared to the human genome (which is approximately 23,000 genes), the genetic aspect of the gut microbiome highlights the potential for it to support human health.

What Makes a Healthy Gut Microbiota?

A wide range of factors can contribute to a healthy gut microbiome with a key measurement of a healthy gut microbiome being microbial diversity.

The diversity of the microbiome refers to the range of organisms within the gut microbiome with greater diversity indicating better stability of the gut. It has been reported that a greater diversity of the gut microbiome is associated with better health and reduced disease.

A variety of factors have been shown to influence microbial diversity and the health of the gut microbiome.

These include:

- Mode of delivery (natural birth or c-section)

- Early life feeding (breastfed or bottle fed)

- Diet

- Age and sex

- BMI

- Antibiotics [Source: PubMed]

C-section Delivery and the Gut Microbiome

The colonisation of the infant’s gut microbiome commences during the development of pregnancy. Another significant influence is the exposure to microbes during delivery.

Both natural (vaginal) births and c-section deliveries expose the infant to a microbiome that influences the development of the gut microbiome, the balance of the microbes via each of these modes of delivery is different.

In a vaginal birth, the infant is exposed to microbes from this region which results in the initial colonisation by organisms such as Lactobacillus, Prevotella and Sneathia. [Source: PubMed]

During a c-section (caesarean section) delivery, the newly born is exposed to the microbes and flora on the skin. This leads to a higher representation of microbes in their gut microbiomes that are commonly found on the skin. These include Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium and Propionibacterium species. It is also common for c-section deliveries to involve antibiotics being given which can further impact the gut microbiome and microbial diversity.

Those delivered by c-section also have a reduced diversity of their gut microbiomes. As mentioned previously, this indicates a less stable and less healthy gut microbiome.

Due to the role of the gut microbiome in immunity. This may partly explain why infants delivered by c-section may be at an increased risk of developing allergies when compared to those delivered naturally. [Source: PubMed]

Breast Milk, Breast Feeding and Gut Health

The type of milk consumed in early life influences the development of the gut microbiome. There are several ways in which breast milk differs from formula milk.

This includes the presence of beneficial bacteria (probiotics) in breast milk as well as a broader spectrum of nutrients and prebiotics (HMOs). This can influence the balance of the gut microbiome with higher concentrations of Bifidobacterium in the gut microbiome of breastfed individuals. [Source: PubMed]

Interestingly, formula-fed infants have a more diverse gut microbiome when compared to those who are breastfed. This may be indicated that some of the benefits of breastfeeding may be unrelated to the gut microbiome. For example, how it can support the development of the immune response in the individual. [Source: PubMed]

Gut Microbiome Diet

The gut microbiome (microbiota) is a dynamic environment which means it alters and adjusts within a short amount of time following changes in diet and food intake. This can involve and result in certain strains of bacteria in the microbiome increasing leading to specific health benefits in the individual.

For example, it’s well documented that those eating a higher meat time will have a different balance of gut microbes when compared to those eating a diet with a higher proportion of plant foods. The can influence the microbiota in a way that makes it highly individualised, with 2 people having 2 different microbiomes.

Those consuming higher amounts of starches have been found to have higher amounts of the Bifidobacterium species which produce enzymes to digest these starches. This can be considered a beneficial adaptive response from the gut microbiome, to aid in digestion. Part of this beneficial effect of increased species such as Bifidobacterium is that they also support aspects of gut health such as balancing gut inflammation, supporting the gut lining and helping transit time. [Source: PubMed]

The opposite is true when viewing the typical Western diet. This is a general dietary template that includes high amounts of saturated fats and refined carbohydrates. The result of which is the increased levels of organisms such as Bacteroides and Bilophila which have been associated with poor gut and digestive health. [Source: PubMed]

Do Antibiotics Damage the Gut Microbiome?

The gut microbiome can be significantly impacted by antibiotics. This can depend on the type of antibiotic as well as how frequently they’re used as well as the initial balance of the the microbiota.

One result of the use of antibiotics is the impact on the balance of the gut microbiome. This imbalance in the gut flora is referred to as dysbiosis, which can be viewed as a reduction in the beneficial organisms and/or an increase in the potentially harmful organisms. The result of this is a gut microbiome that is not as diverse or resilient. [Source: PubMed]

An example of this, is the occurrence of clostridium difficile (C. difficile or C. diff,) infection following antibiotics. [Source: PubMed]

As well as antibiotics, other factors that contribute to dysbiosis include diet, infection and eating disorders.

The changes in the gut microbiome that can result from antibiotic treatment can increase the risk of other conditions such as metabolic dysregulation as well as an increased risk of infection.

Research has also found that antibiotic usage in the first year of life influenced metabolic function and increased the body mass index of the patient in later life. [Source: PubMed]

The Gut Microbiome, Immunity and Inflammation

The gut microbiome plays a key role to support immune function and inflammation in the gut and the human body. The benefits of gut microbes are largely due to the products they produce when supplied with certain sources of energy, one of which is dietary fibre. Therefore, the food we eat partly feeds the gut bacteria to influence human health.

The human digestive tract does not produce the enzymes required to digest the fibre contained in a wide variety of plant foods (fruits and vegetables). This means that humans are not able to release and absorb energy and calories from these fibres.

However, certain species of gut bacteria produce the enzymes required which allows them to digest these fibres via the process of fermentation. This fermentation process of fibre that takes place in the human digestive system by the gut microbiome generates short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). These are then absorbed by the gut with a variety of health-promoting aspects which include anti-inflammatory and immune balancing effects. [Source: PubMed]

Other compounds produced by the gut microbiome help to support gut health in a range of other ways that include:

- the maintenance of gut epithelium and thereby the integrity of the gut wall (eg, reducing gut lining damage/leaky gut)

- production of vitamins and nutritional compounds

- interactions with several key immune system signalling molecules and cells, activating and inhibiting specific responses [Source: PubMed]

The way in which the gut microbiome and the gut bacteria within the digestive tract support human health is often by stimulating the body’s own processes.

This can be via the stimulation of anti-inflammatory mechanisms within the gut as well as stimulating certain parts of the immune system that regulate immune processes and inhibit inflammation. [Source: PubMed]

The Gut Microbiome and Cancer

Several studies have investigated the balance between the human microbiota, cancer and inflammation. As mentioned, changes to the balance of the gut microbiome are commonly reported with alterations to the gut microbiome and this has been reported in several types of cancer.

These cancers include:

- Pancreatic cancer

- Gastric cancer

- Colon cancer

- Liver cancer

- Breast cancer

- Prostate cancer [Source: PubMed]

It has also been reposted that the gut microbiome influences the formation of tumours local to the lining of the gut as well as influences the response to the treatment.

A 2014 study found that administering antibiotics to mice with colon cancer reduce the progression of the cancer. Due to the role antibiotics play in influencing the gut microbiome and the balance of the gut bacteria, this likely highlights the role of the gut microbiome in colon cancer. [Source: PubMed]

Part of the role the gut microbiome plays in cancer development and progress is due to imbalances in the gut bacteria-producing metabolites that may contribute to genetic instability.

The balance of the gut microbiome can contribute to inflammation in the colon. This can be due to gut imbalances (dysbiosis) leading to an increased level of specific pro-inflammatory organisms in the intestinal microbiota.

It is also well-documented through research studies that inflammation alters areas of the body, making them more susceptible to cancer development. For example, the long-term inflammation seen in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a strong risk factor for colorectal cancer. [Source: PubMed]

The Human Microbiome and Leaky Gut

Leaky gut is also described as intestinal permeability and is regulated by the gut microbiome and gut bacteria. One aspect of this is that certain species of bacteria may promote a leaky gut. This increase in the permeability of the gut lining leads to microbes or inflammatory compounds translocating from the gut into general circulation.

The release of these compounds from the gut microbiome into circulation may then trigger the release of cytokines that may then lead to an inflammatory response. [Source: PubMed]

Additionally, the cells along the gut lining may also influence inflammation and gut permeability. This is where the gut microbiota can transport parts of the bacterial wall to immune cells which can then increase inflammation. This inflammation may happen within the gut or the gut lining but also potentially systemically (e.g. throughout the body).

Also Read: The Gut Microbiome & IBS

The ongoing nature of this inflammatory response can be described as chronic inflammation. While at a low level, the persistent nature of this inflammation has been linked to the development of a range of health conditions.

These conditions include:

- inflammatory bowel disease (IBD such as Crohn’s disease or Ulcerative colitis)

- diabetes

- cardiovascular disease [Source: PubMed]

What is Microbial Diversity?

A diverse gut microbiome indicates that the gut has a higher degree of stability. This is partly due to the presence and overlap of functions between certain organisms.

This means that if a certain species of bacteria was to ‘go missing’ from the gut, another organism would be able to cope with the responsibilities. For example, how to digestive certain foods.

Many of the aspects of modern life can influence and reduce microbial diversity. These are factors such as stress, pollution, dietary patterns and medications.

A loss of diversity is associated with an increased risk of asthma and allergy in children as well as obesity, insulin resistance, autoimmunity and systemic inflammation. [Source: PubMed]

How to Improve Gut Health and Microbiome Diversity

Gut health studies indicate that the diversity of the gut microbiome has reduced over recent generations.

A great deal of this can be due to factors associated with the Western world and modernisation. This includes an overly clean environment and over-sanitisation.

The most common causes of this reduction in diversity appear to be:

- Clean drinking/bathing water (reduce bacterial exposure)

- Increased rates of C-sections

- Increased rates of pre-term and infant antibiotic use

- Widespread antibiotic use throughout life

- Reduced breastfeeding rates

- Increased use of antibacterial soaps, creams, and sprays

- Ultra-processed foods

While we may not be able to change several of these, there are many areas of the gut we can support to improve gut health and microbial diversity.

How Does the Gut Microbiome Develop?

The first exposure to bacteria humans have is while we are still developing inside the womb. The second is the bacteria we’re exposed to upon birth. This does depend on the mode of delivery with c-section births and natural deliveries both exposing the newborn to different microbes.

These factors also relate to the microbiome of the mother as she is essentially only able to pass to her offspring the microbes that she has.

These factors that impact maternal microbial diversity include:

- antibiotic exposure and length of use

- if antibiotic cocktails were used (ie for H pylori infections)

- antibiotic use during pregnancy & at birth

- dietary patterns.

- PPI exposure during life and pregnancy

- food additives and environmental chemical exposure.

This depleted ecosystem provides the first inoculation of beneficial bacteria to the infant which seems to start them on the back foot. [Source: PubMed]

Do Medications Impact the Gut Microbiome?

A wide range of medications can influence the balance of the gut microbiome.

These medications include:

- Antibiotics

- PPIs (proton pump inhibitors)

- Opioids

- NSAIDs (eg Ibuprofen)

- Antipsychotics

- Statins

The use of antibiotics can lead to dramatic changes in the gut microbiome, resulting in dysbiosis. With higher strength antibiotics as well as repeated usage leads to larger changes.

Proton pump inhibitor medications such as omeprazole and lansoprazole can also contribute to microbial imbalances. While these medications are used as a treatment for reflux, peptic ulcers and H Pylori, alterations in the gut microbiome can result from long-term usage. In particular, increasing the risk of developing SIBO or a C. difficile infection.

Additionally, antipsychotic medication alters the balance of the organisms within the gut. This may be a central factor that contributes to the metabolic syndrome and weight gain commonly seen when taking these types of medications.

Opioids are well known to contribute to digestive symptoms such as constipation, but they can also contribute to disruption of the gut barrier. The same is true for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) such as Ibuprofen. This can be due to these medications reducing the blood flow to the gut and weakening the gut bacteria.

Statins are a medication used to treat elevated cholesterol. However, they can also influence the balance of the gut microbiome and contribute to digestive symptoms. [Source: PubMed]

Food Additives and the Gut Microbiome

Consumption of artificial sweeteners can also alter the bacteria in the gut. Sucralose has been shown to reduce the levels of both bifidobacteria and lactobacilli groups of bacteria as well as increase the pH of the colon.

The change in the pH, pushing the gut towards a more alkaline environment allows non-beneficial bacteria to thrive.

Saccharin shows similar changes with increases in bacteroides and staphylococci and decreased concentrations of Lactobacillus reuteri and Akkermansia muciniphila.

In addition, these changes in the microbiota are associated with the development of glucose intolerance. [Source: PubMed]

Do Chemicals Damage the Gut Microbiome?

Chemicals from household products are also seen to be having an impact on the gut microbiome.

Diethyl phthalate (found in plastics), methylparaben (anti-fungal preservative in make-up and moisturisers), triclosan (anti-bacterial preservative in toothpastes) – when administered to rats at doses comparable to human exposure from birth through to adulthood it showed a detrimental impact on the bacteria with “exposure to the environmental chemicals produced a more profound effect on the gut microbiome in adolescents”. Phthalate-free products are available that use natural preservatives. [Source: PubMed]

Best Diet for the Gut Microbiome

Besides medication and environmental compounds, the health of our gut may hinge on our diet. One approach that seems to have an impact on the diversity is a high protein / low carb diet which showed a 50% decline in faecal concentrations of Bifidobacteria in just 4 weeks as well as in several other beneficial species.

The Western diet also seems to impact the gut by, what research call, “starving our microbial selves” through a diet low in polyphenols, low in total dietary fibre and high in processed foods and food additives with additional high exposure to environmental chemicals.

A good rule of thumb is to aim to eat 40+ different whole, minimally processed plant foods each week which should make up approximately 90% of your plate at each meal time.

These will contain a high amount of resistant starches; polyphenols; prebiotic-rich foods; prebiotic- like foods; gums; mucilages; pectins; soluble and insoluble fibres.

The prebiotic-rich foods that specifically stimulate the growth of beneficial bacteria are found in a range of foods with the most pre-biotic rich being garlic, onions, leeks, Jerusalem artichokes, lentils, haricot beans, lima beans and red kidney beans. [Source: Pubmed]

Polyphenol Rich Foods Include:

- Fruits – Black elderberries, black currants, blueberries, cherries, strawberries, blackberries, plums, raspberries, apples (red), black grapes

- Nuts and Seeds – Flaxseed meal, chestnuts, hazelnuts, pecans, black tahini

- Vegetables – Purple carrots, red carrots, purple/red potatoes, red cabbage, spinach, red onions, broccoli, carrots (orange), red lettuce

- Grains – Red rice, black rice, red and black quinoa, whole grain rye bread (sourdough)

- Other – Black olives & olive oil

- Other items with prebiotic-like effects are – almonds, green tea, brown rice, carrots, blackcurrants and dark cocoa. [Source: Pubmed]

Fermented Foods for the Gut Microbiome

Fermented foods have been shown to increase the diversity of the gut microbiome and microbiota. They have also been shown to decrease levels of inflammation in the gut. With larger improvements occurring with increased amounts consumed.

Low diversity in the gut microbiome is linked to poorer gut health and is also associated with conditions such as diabetes. Therefore, supporting the gut with fermented foods can improve overall well-being, evening in healthy people.

This can be in part due to the ability of these fermented foods (that include sauerkraut, kimchi and kefir) to introduce beneficial organisms to the digestive tract.

In addition to this, fermented foods also introduce bio-active peptides as well as SCFAs (short-chain fatty acids) into the digestive system. These are created during the fermentation process and support aspects of gut health such as the strength of the gut lining and an appropriate immune response. [Source: Stanford]

Gut Microbiome and Brain Health

The microbiomes in the human gut microbiome can influence the health of our brains. This can be influenced by the balance of the gut microbiome, and factors such as diet and the fibre intake from food.

The link between gut health and brain health highlights the link between the gut and the gut microbiome, and overall well-being. For example, the factors that influence gut health can also have a systemic impact on human health and well-being.

The role of foods and the dietary fibre that humans eat is not only to support bowel movements but also to act as a food and energy source for the gut microbiota. Once well-fed, these organisms produce beneficial compounds called short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

This is where a diet high in fermentable fibres can support gut health which in turn supports brain health.

While these SCFAs support the health of the gut lining they also enter general circulation where they support other areas of the human body, including brain health.

SCFAs have been found to be in the lower levels of those with depression. In addition to this, Butyrate, one of the main SCFAs, was found to have an anti-depressive and anxiety-reducing effect in an animal study. [Source: Science Direct, PubMed]

The Gut Microbiome and Gut Health

The gut microbiome is a central component of how our digestive system functions and supports health. Not only to digest foods but to also support overall well-being and reduce the risk of developing conditions such as diabetes.

Dietary and lifestyle adjustments can be central to supporting microbial diversity and microbiota health.

Working to optimise health or supporting a medical condition can begin with support gut health and the gut microbiome.